You’ve got your shitty first draft… now what?

When I finished the manuscript of my second novel I had one thing on my mind.

To make sure I didn’t make the same mistakes I did with my first novel.

For my first, I had followed all the rules of writing, read all the books, and worked hard until it was finished. I put it aside for a month, came back to it and discovered (in horror) that it was terrible. Just so bad.

When I finally gained the courage to start editing, I had no idea how to do it.

I would rewrite scenes and it would be the same piece of crap in a different order. I would polish up the wording and it would become a shiny turd. Eventually I gave up, put the book in my closet, and told everyone I was working on something else.

So when I finished my second novel, I hunted for advice first.

And I found it almost impossible to find.

Despite many articles, hours of podcasts, and multiple books, I felt like I still did not know what to do next.

So after all that research I decided to write the article I would have wanted to read…

This article should be called “How I Learned To Diagnose My Novel”.

All the editing research I did was helpful, but they didn’t teach me how to know what is shitty about my shitty first draft.

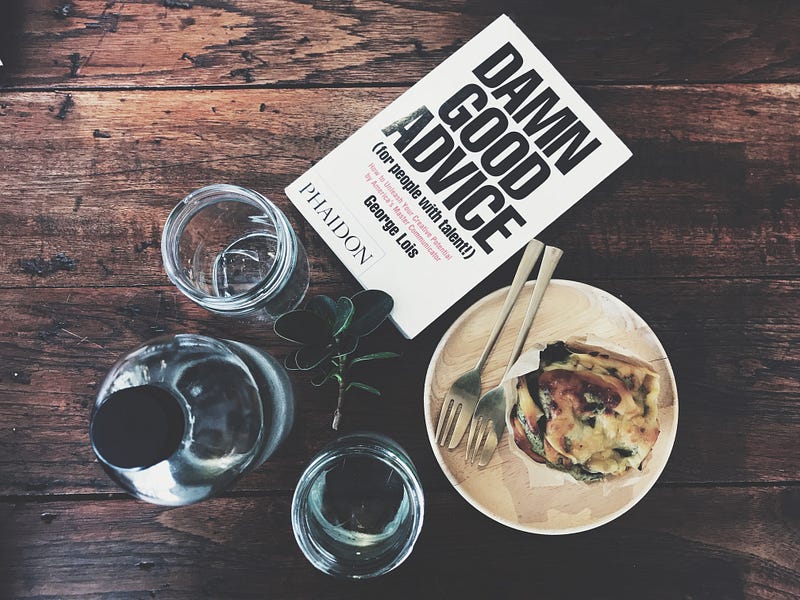

I finally found the rules for diagnosing in The Story Grid by Shawn Coyne and STORY by Robert McKee. I highly recommend you go read both these books, they are great. But they are long. The Story Grid Podcast was also great (specifically Episode 87, Planning The Second Draft), but at 150 episodes it can be a bit of a journey.

But why edit it yourself? Why not hire an editor?

The answer for me came in the Story Grid podcast. It tracks the journey of a professional non-fiction writer creating his first fiction novel while being guided by a professional editor. After two years they finally have a finished first draft. While discussing the second draft, the editor, who literally guided the book every step of the way, said this about his main client and writing partner Steven Pressfield:

“Steve does not ever ever ever send me a draft like the draft you have now. He would never in a million years consider sharing that with anybody. It’s like this very delicate goo that he doesn’t want anyone else to see. That’s what you have right now. A lot of people just want to dump their goo on an editor and have that editor form that goo into something for them.”

This advice seems harsh, but like it or not, unless you want to pay an editor to essentially write your book for you, it is necessary to edit your book first. I took that advice to heart.

Here is how I’m diagnosing/editing my novel:

For the list lovers, this information is summarized again at the end.

First, I put it aside for a few months. This is typical advice but useful. You want to read it with fresh eyes.

Next, read the novel. Hide your pencils and highlighting tools. Read it quickly and ruthlessly, without even fixing spelling errors. You want to become familiar with the book again.

No editing allowed.

Now it’s time for some make believe. Grab a notebook, or note-app, and read it again.

This time pretend you are a famous editor, reading the manuscript of some brilliant writer who always has crappy first drafts and you have this beautiful friendship where you make their work great without any judgements.

Now, as the editor, make five (or more) bullet points for each chapter. Mark down what doesn’t feel right, what you want to change, any ideas you have. Make notes about everything that even sort of feels off, because if it feels off to you, readers will notice it for sure. Don’t make any changes though… you’re the editor! Not the author.

Next you learn how to structure a scene.

This can, and should, be its own post. I’ll do a brief intro here, but if you can go read more about scene structure, it’ll help you in every way.

When I sit down to edit every day, the first thing I do is read the scene/chapter I am on and find the following instances…

Inciting Incident:

Rising Action (Turn):

Crisis:

Climax:

Resolution:

But what do these mean? Let’s answer that… with a story.

Once upon a time there was a guy called Frank. He really wanted to get fit but he’s a big, fat, lazy guy.

Inciting Incident — What happens to get the characters moving in the chapter.

Every scene has to have an inciting incident. Something has to happen otherwise it is just description. This can be anything from a bomb exploding in the bathroom to the character wanting a sandwich.

One day Frank decided he had enough of being a slob and decided to do some push ups.

Rising Action (Turn) — This is much more than what happens next. It must ‘turn’ the action, which basically mean that something occurs which cannot be undone.

Either the character learns something that they cannot unlearn, or they do something that stops them from going back to basics. Even if they end up in the same situation they started, they will have experienced something that changes them in some way. This is where a lot of the tension and conflict come from.

Frank got on the ground, managing to shove himself into plank position, and then realized he was hardly able to hold himself up. His arms were quivering, sweat was pushing itself out of his forehead — he couldn’t do a push up.

Crisis — This is the question moment. Will they or won’t they?

I literally phrase it like a question for each scene.

Will Frank try to do a push up or won’t he?

Climax — Answer the crisis question. They will! Or… They won’t!

This is what the readers have been waiting for. If your scene does not have a climax it is probably because the Turn was weak.

Frank… decided to try it! He lowered himself down, everything shaking, a guttural cry escaping as he reached the bottom. But he had done it! He was supporting himself… and it even felt easy! He relaxed, still holding himself aloft. His heart soared, until he glanced down. His stomach pooled on the ground, holding him up, his entire weight resting on it. His push up was a failure.

Resolution — Tell the audience how the character reacts to this climax.

Do they celebrate and move on to the next inciting incident? Do they give up and go home? Do they quit their job and retire to Mexico?

Frank quit. He returned to the couch, deciding his dream of being fit was a nice fantasy. He then proceeded to watch another 1000 hours of Netflix until he died.

See how each scene/chapter fits into the structure above? I literally write it at the top of each re-write page, then plug in the exact moments to make sure it all works.

Mymost common mistake is that I don’t have enough Turn. Many of my chapters miss that moment of no return — I get caught up in description and dialogue. So I rewrite those scenes, putting in a realization or an action that can’t be undone. This inevitably leads to more conflict, which makes everything interesting, and my chapter becomes better.

You should now have a diagnosed chapter. What next?

Rewrite the scene. Follow your new scene structure layout. Get your bullet points (that you made as a make-believe editor) and incorporate them. Answer any questions you had and fix anything that felt off.

Then do it for every chapter and scene in your book.

If this seems like a lot of work — it is. So much work. But it is necessary. You need to diagnose your book and fix it.

This is a painful but rewarding process. Each scene that I hammer out becomes something that I am almost proud of. Maybe after doing it three or four times for the whole book and I’ll be able to edit out the ‘almost’ in that last sentence.

Hopefully I’ll do all this in my first draft for my next book, but for now I do it one scene at a time. I wish you luck doing the same.

That all being said, if anyone else knows any other good ways to structure and diagnose their work, please let me know. I am very aware that I have a lot to learn.

For those who revisit articles, here are the steps in a nice numbered list.

-

- Put it aside for a month or two.

- Read the novel fast and furious — no edits!

- Become a make-believe editor. Make five (or more) bullet points for each chapter. Mark down what doesn’t feel right, what you want to change, any ideas you have.

- Inciting Incident — What happens to get the characters going in the chapter.

Rising Action (Turn) — The actions that ‘turn’ the story, which basically mean that something occurs which cannot be undone. Either the character learns something that they cannot unlearn, or they do something that stops them from going back to basics.

Crisis — This is the question moment. Will they or won’t they?

Climax — Answer the crisis question. They will! Or… They won’t!

Resolution —How the character reacts to this climax. - Write these at the top of each re-write page, then plug in the exact moments to make sure it works.

- Rewrite the scene. Follow your new scene structure layout. Get your editor bullet points and incorporate them. Make sure you answer any questions you had and fix anything that felt off.

- Do it for all the scenes in your book.

- Do it over and over again until you’re proud of it.

Originally published in the Writing Cooperative at https://writingcooperative.com/